The Augmented Realist Manifesto, Part 2

Speculative endings from alternate futures

If you haven’t yet, be sure to read part 1 of The Augmented Realist Manifesto before proceeding.

So what would be good? What’s bad?

So, AR is coming, for better or worse. What’s better? What’s worse?

Example 1: Convergence and the Attention Economy

Imagine a world with no more screens. Anything that has a screen - your TV, your computer, your phone, your car, your watch - they’re gone. Redundant.

All the physical screens are no longer necessary because anyone can put anything anywhere in their vision, screen-shaped or otherwise. If they want to have a tiny feed or a colossal screen hanging out in their field of view, they can do that.1

For evidence that this convergence is likely, consider that within 14 years of the first iPhone launch, it was already common to see restaurants without any physical menu offered, rather only a QR code on the table — the assumption being that everyone has an internet-connected QR reader and screen on their person, making the printed item redundant.

A Better Outcome: Wearers are in control over how they see the digital world around them. Augments are found and filtered by a client-side permissions structure entirely in the control of the user.

Multiple people can see the same augment, so, e.g., a movie theater is anywhere you want, with a screen as big as you want, visible to whoever wants to see it. Any two or more people can choose to share the experience of any digital thing at any time.

There are no more computers, per se, nor smartphones, nor offices as we think of them. Instead you can summon an infinitely flexible personal workspace with as much or as little screen real estate as you want, anywhere you want it, in the position you find most convenient or unobtrusive or ergonomic.

Relatedly, no more TVs cluttering up spaces and distracting from human connection unless you want them.

Relatedly, no more physical advertisements. No billboards, posters, etc. in the built environment. They’re too expensive to deploy and maintain, too static, and likely to be covered by other augments anyway.

Overall, fewer devices means less carbon and e-waste from the electronics industry - one device per person serves the purpose of every display and computer currently in use and more.

A Worse Outcome: We get a world where vertical integration, defensive incompatibility, and irresistible freemium business models collude to wrest control over reality from users’ senses.

(Virtual) billboards and ads everywhere. Advertising on every surface, on top of people, on top of live sporting matches you’re watching in person, on your pet, on your food, on the sidewalk, in the mirror, everywhere.

Animated product packaging, with sound, and you can’t stop it. Ads literally floating in front of your face. You can’t look away, you can’t turn it off, and for some hardware, it doesn’t help to close your eyes.

Lest you think we wouldn’t allow our senses to be cluttered that way, consider that TV is about 16% commercials (cable TV - the kind you pay for!), radio 26%, the model being that the content is ‘free’ or subsidized. The same can be found on the web and streaming video. The market has strongly endorsed this model.

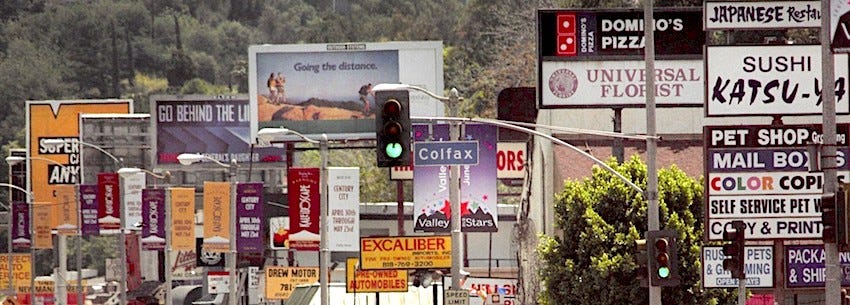

We even do it in ticketed, live sporting events, and pay-per-view cable:

… and in our cities …

And, yes, Times Square and Dōtonbori are tourist attractions in part because of the ads, but when everywhere is Times Square, the ads lose their charm.

Advertising has been a fixture of the commons going back at least to ancient Rome, and it’s the engine behind two of the top ten largest companies of all time, both of whom are in the running to make the shortlist of owners of this AR future. History tells us ads are likely to come along into this new medium as well, where the sell is piped almost directly into your brain.

If you think you personally won’t participate in a system in which your attention is used as payment for a service, there are, nonetheless, billions of other people who likely would make that exchange. They’ll compromise because the utility of wearing will be too great to pass up, and because they won’t have the wealth to afford unsubsidized hardware without the adware.2

Example 2: Platforming vs Open Access

Imagine you’re a shop owner. You want to be able to control the appearance of your establishment in augment space - to provide visual interest, information, and context for your products, or perhaps to offer way-finding in larger stores.

Or maybe you have a quick-serve restaurant and you want to have that digital menu at a few key locations around the restaurant. Or maybe you’re a homeowner or renter who wants to decorate and add utility to your own space. Or maybe you’re an artist and you want to share your sculptures / paintings / interactive softworks.

The common thread here: you want to provide augments that don’t directly produce revenue from their users. They don’t ask for payment. There is no business model attached to creating these things - they’re simply useful, or beautiful.

A Better Outcome: You use a no-code solution, or your own coding skills, or you hire a developer to help you make the thing you envision, and then you publish it in a place where your target audience can discover it through proximity, physical indicators, search, suggestion (AI), word of mouth, etc.

Consumers use AR devices that can access something like the web we know today, executing arbitrary code found through a variety of means, with no intermediaries between publisher and viewer.3

You pay as much as you’re willing to pay to make the experience you want, and you own it outright, something like a web page. You can self-host, cheaply. You can monetize if you like, or not. You can promote by the means of your choosing. You can choose your tech. You can change your tech.

A Worse Outcome: Every AR device in popular use is tethered to one of several vertically-integrated ecosystems, including an app store, complete with ever-changing terms of service, shifting and lopsided privacy policy, strict rules around monetization, and a challenging and idiosyncratic discovery landscape.

If you want to control your experience as much as possible, you must, for each AR ecosystem you want to reach, engage developers, build an ecosystem-specific app, attempt to get it published in the app store4, pay the ecosystem its cut if you monetize, and advertise within the app store to attempt to find users.

Will there be in-ecosystem platforms that let you do this? Absolutely. Think Instagram or Medium or YouTube, or, in the restaurant menu example, Grubhub. Those platforms don’t require you to roll your own engine and find your own audience - they handle it for you.

If you use the AR equivalent of these platforms to make this sort of thing, will you own your work and control its presentation? Will you be able to prevent the platform from monetizing your augment on their own behalf, or selling your information, or your customers’ information, or injecting advertising in between you and your viewer? Precedent suggests not.

But those platforms will offer the ability to accomplish a version of your goal without requiring you to modify your business model to be extractive, or to have one at all. Without their cross-platform creation and discovery tools and their baked-in audience, your product would need to be monetized to offset the technical lift required to reach so many disparate hardware and software configurations.

As hard as it is to target anything more complex than a simple native application to iOS and Android today, imagine if there were instead 5+ popular AR OSes, each tightly coupled with hardware-specific APIs and idioms, each with its own relationship to the physical world.

Any intention to offer utility or entertainment or beauty to the most people possible would seem quixotic without something like an AR ‘web’ — a cross-platform markup language and an AR-native search and discovery system to lower the participation friction to the point that creators don’t need to raise money or give away their work to participate.

In this scenario, as has been the case with smartphones, many projects will by necessity choose to target only one OS. The negative consequences of that fragmentation are ameliorated in today’s environment by the (mostly) universal and ubiquitous web, which is as cross-platform as software gets.

Our flat, text-centric web will still have its place in AR: for still, focused perusal of the information-dense stuff we consume today. Its generational wealth of information and utility won’t go away, per se, but the data and markup of today’s web is largely incompatible with AR’s spatial computing paradigm, and is ill-suited to sharing space with the body. Using the web in AR will feel like editing a spreadsheet on your smartphone.

We’re going to need an equivalent in AR, or we’ll never have anywhere to call our own.

Example 3: Balkanization and Participation Friction

Let’s say you’re an entrepreneur in the entertainment industry — an attractions developer. You want to make the AR equivalent of a AAA video game5. This is going to be a huge project - a site-specific cross between a theme park and an MMO, woven into a physical location. Your team estimates it will take about 7 years and $340 million, minimum, to complete. You intend to make your money back via ‘ticket’ sales, subscriptions, and maybe in-world ads and product placement.

A Better Outcome: You develop your project, publish it to a publicly-discoverable server, and advertise its existence anywhere you see fit, because anybody with gear can find it and run it. Your audience pays you directly with any payment method you choose to accept, like a website, or a PC video game.6 You deploy updates whenever and however you like. Your development is constrained only by your ambition and your finances.

A Worse Outcome: You fragment your front-end dev budget into X buckets, where X is the number of competing walled-garden AR systems you want to reach. You fight to get your project approved and released into the app stores of each of those platforms, as you do each time you release an update, which is constantly, because you’re running a theme park.

In order to be discovered, you must dedicate resources to app store SEO and advertising on each ecosystem as well. You can only create experiences that comply with the TOS of the various ecosystems, and you can only accept payments via their terms, which take a ~15-30% cut of all revenue, including, on some platforms, things like food ordered from real-world vendors via your digital systems.

The ecosystems who are, in effect, both your partners and your captors, can, at any time, change the terms of their deal, and in so doing completely upend or outright destroy your business model.

Consequently, you greatly diminish your ambitions to account for the redundancies and overhead, and quickly consider finding revenue in places you would ideally never go looking. Your customers’ experiences suffer accordingly. Children and adults alike experience less joy for more money. The world is a little shittier.

Example 4: Your Personal Extension in Augment Space

Let’s say you want to augment your physical appearance. You want your clothes, or your hair, or your ‘makeup’, to have a digital component. Or you want to offer information or even some utility to people in your proximity — something like a business card or an FAQ or a menu of services or an art gallery.

Or let’s say you are a property owner and you want to extend the physical architecture of your building into virtual space. Interior decoration and functionality for your house, say, or for your commercial building.

A Better Outcome: While anyone has the freedom to attach augments to any thing and any place they wish, you, as the rightful owner of your person or of your property, have the ability to dictate the ‘canonical’ augment. Viewers can elect to prioritize canonical augments in their experience selectively, through dynamic permissions structures, e.g. allowing all of their friends or contacts canonicals through by default.

Your augment is, like any other augment, visible to all, carrying arbitrary code that viewers can allow through or block with a granular permissions scheme like the one we have on smartphones today. Users might allow audio but no visual permissions. They might allow an augment to run sandboxed code but not to reach out to the internet, etc.

Anyone has the freedom to ‘speak’ by augmenting anything, anywhere, whether their contribution is art, opinion, scholarship, journalism, or graffiti. They simply anchor their augment to a person, place, or thing. Speech - unpopular speech and even hate speech - amasses on persons and places of any renown.

Viewers and the intermediary tools they use for search and discovery employ different reputational, rating, AI recommendation, and social methods to bubble up relevant augments and suppress the things they don’t want to see, more or less invisibly, and in realtime (yes, ‘the filter’, and ‘the algorithm’, but ‘running local’ and in the users’ control).

A modular AR architecture allows users to pick and choose how augments do or don’t make their way into their experience, mixing and matching search, filtering, firewalling, etc. tools as they see fit. They use these tools to shape the flow from the augment firehose sitting on top of the world’s ideas, as, e.g., the American flag or the White House or an image of the president is encrusted with millions or billions of augments.

A Worse Outcome: recognition and tagging of the things, places, and people of the world is baked in to AR systems at the OS level, or is a done by AR applications themselves. That means there is no central place for a person to claim ownership of their identity, and no consistent way for them to have a voice in their extension into augment space.

Each major service offers some platform or OS-specific ‘Memoji’ system that only appears to others if they are running the same OS or have installed the appropriate cross-platform application. Even then, creators are constrained to making only what the system allows them to create. Precedent tells us this will be a narrow possibility space of cartoon avatars with zero ability to attach payloads of arbitrary code and assets.

Those who wish to offer augment-space extensions to architecture need to hope that their potential viewers have installed the platform app on which they published their augment, and that it’s running, and that the user discovers the augment.

If these digital architects and interior designers and property owners care enough, they can, of course, pay to advertise in-app, as discussed above.

Or they can participate in the surreal trend of putting the platform’s logo on their marketing or in their physical space, as many do with Twitter and Facebook today.7

In this fragmented environment, there is simply no way for creators to attach augments to the people, places, and things of the world in a way where they can expect the right people to find it. There are too many places to be.

Because the linkage from recognition to search to recommendation to presentation is so tightly coupled, users have little to no control over the search ranking, filtering, and suggestion mechanisms at work in the platforms they use, and their access to the world’s information, or to an audience, is subject, as we say today, to ‘the algorithm.’

What are we going to do about it?

I hope I’ve convinced you — the shit is going to hit the fan and we are standing underneath it. I propose we do something before it’s too late.

There remain, superimposed, good futures and bad futures ahead of us.

We should pick a good one … and we shouldn’t let the market decide what kind we get.

That’s the focus of this blog. How do we, serfs that we are (in which I include those who work at a Meta / Apple / Google / Microsoft / Snap / Niantic / Epic / Magic Leap), rather than take what we’re given, make the augmented future we want come to pass?

Follow me here on Substack as I explore, like a Soviet Futurist, hypothetical utopian architectures of AR. How could it work for us? How can we build it?

Look out soon for a podcast and/or YouTube thing which I envision to be three parts Pee-wee’s Playhouse to one-half part Crossfire with Newt Gingrich.

We’re focusing here on 2D, non-spatial computing and consumption. We’ll speculate later about how long those paradigms will persist.

By way of example, witness Facebook’s entrée to Myanmar, in which, by way of carrier partnerships, Facebook data was not counted against bandwidth caps, making Facebook, by dint of cost, the de facto internet in the country, to disastrous results. https://www.bbc.com/news/world-asia-55929654

Ignoring the intermediaries of the ‘browser’ and search and wireless networks, some of which will be major areas of focus on this blog.

Nilay Patel calls this ‘getting past Eddy Cue’

alas ‘ARG’ is taken by something cool but unrelated

Acknowledging here that for some games, the Steam platform solves distribution and discovery problems, for which game developers often pay as much as 30% of the gross take, but that’s not the only way games have to connect with customers and distribute code. Acknowledging also that there are vertically-integrated game consoles that offer a great experience for many customers, but that increasingly studios find it impossible to release AAA titles on competing consoles.

In my eyes this is about as vivid a sign of dysfunction as you’ll find, however subtle.